Daniil Kharms was an avant-garde, absurdist writer of the early 20th century.

I first encountered his poetry at the age of 5 — that’s 1993, when Yeltsin used tanks against the Parliament — in a collection of absurdist rhymes titled Everything Upside Down1. I had already learned how to read the year prior but still enjoyed listening to my mother reading poems to me.

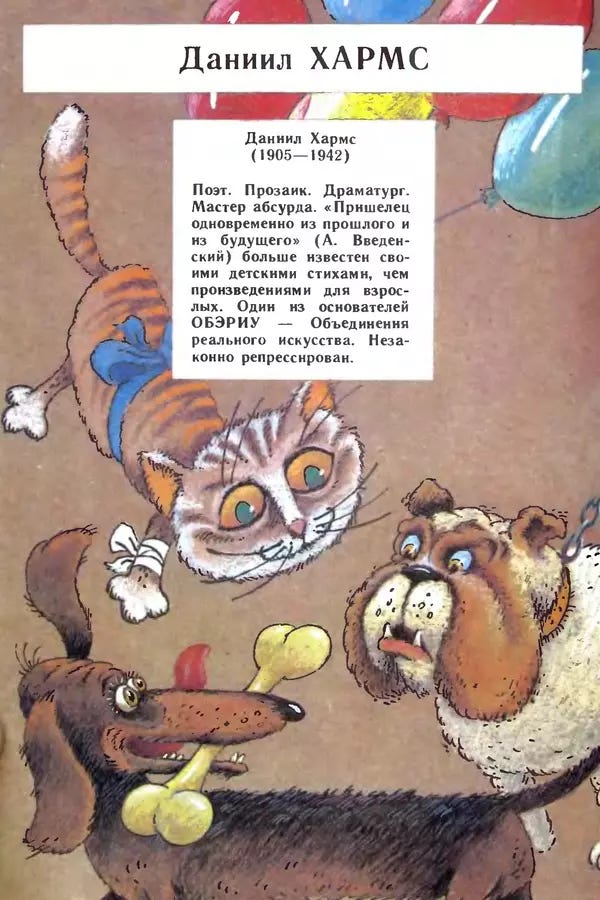

The first half of the book consisted of translations from American and European authors, and the second of poems by Russian authors. Each had a short little blurb about them.

Here’s one for Kharms:

A poet. A prose writer. A playwright. A master of the absurd. This “visitor from the past and the future at the same time” (quote by A. Vvedensky) is better known for his poems for children than his works for grown-ups. One of the founders of OBERIU — the Association for Real Art. Unlawfully persecuted.

The Russian word I translated as “persecuted” is репрессирован, “repressed.” It’s a term used for the victims of Stalin’s purging campaigns, during which tens of millions of people were imprisoned or killed. I’m sure I didn’t know that word as a five year-old, and I’m sure I’ve asked my mom what it meant. I don’t know how she replied.

Kharms was born in 1905, in the Russian Empire. His father, Ivan Yuvachev, had by that time spent a dozen of years in prison camps for his membership in the revolutionary group The People's Will and involvement in subversive acts against Tsar Alexander III; it was in the camps that he underwent a religious transformation and became a philosopher.

Kharms himself was arrested two times: in 1931, for membership in “a group of anti-Soviet children's writers,” and in 1941, for spreading “libelous and defeatist mood” at the time of war. He died of starvation in 1942, during the siege of Leningrad, in the psychiatric ward of the Kresty prison.

Below are a few of his works — not children’s poems — that I first encountered in my teens and that, I think, express something quite foundational about the Russian experience and, for that matter, the human predicament broadly.

See also:

Wyrld, by Daniil Kharms

The Changing of the Wheel and Little Knives, on my post-Soviet childhood

Tumbling Old Women

One old woman, out of excessive curiosity, tumbled out of her window and fell to her death.

Another old woman stuck her head out the window to look down at the one who had fallen, but, out of excessive curiosity, she too tumbled out of her window and fell to her death.

Then a third old woman fell out, then a fourth, then a fifth.

When the sixth old woman fell out, I grew weary of watching them, and went to the Maltsev Market, where, they say, a blind man was gifted a knitted shawl.

<19..>

Incidents

Once, Orlov overate mashed peas and died. And Krylov, upon hearing about this, also died. And Spiridonov died of natural causes. And his wife fell off a cupboard and also died. And Spiridonov's children drowned in a pond. And Spiridonov's grandmother started drinking and took to the road. And Mikhailov stopped combing his hair and got scabies. And Kruglov drew a lady with a whip and went mad. And Perekhrestov received four hundred rubles by telegram and got so conceited that they kicked him out of his job.

All good people, and yet they just can't seem to get a solid footing in life.

<August 22, 1933>

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Psychopolitica to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.