There’s a sign in a street in Madrid with the images of a dagger, a human head on a plate, and a bloodied, severed head of a ram. This is the Street of the Head. I look up the story.

Sometime during the reign of Philip III (17th century), a servant of a rich priest, who lived on this street, beheaded his master, took his gold and fucked off unnoticed. The murder was never solved.

Years later, he came back to the city, now in knight’s clothes. He bought a ram’s head on a market and, having no servant of his own to bring it home for him, carried it under his cloak. A cop noticed the trail of blood he was leaving behind and stopped him to ask what it was he was carrying. The man replied, “What do you think? The head of a ram I just bought,” and went on to present the head. To his surprise, the head he now held in his hands was that of his former master. Shocked, the killer confessed there and then.

When they brought him to justice — by hanging in the main square — the head was carried in front of him on a silver plate. As soon as the sentence was carried out, it turned back into the head of a ram.

In the town I am from, most streets had no names at all, and the ones that did, were called things like the Apple-Tree Alley, the Birch-Tree Alley, or the School Street. There was nothing quite like the Street of the Head.

At the end of my first day in Madrid, tired and weary, I stop by a ramen place next to my hotel and order some food and a whiskey. The waiter looks happy; he puts a glass and a bottle on my table and leaves.

I look at him quizzically.

“Serve yourself, sir. Finally, someone who drinks.”

Back in Málaga, on a walk with my dog, I first hear and then see a large crowd of people marching down the street, chanting slogans I (shamefully) don’t understand. The sings they are carrying are easier to interpret — some I have seen already and learned to recognize by now, and others I can look up via ChatGPT.

They’re all about tourism and gentrification: “This used to be a neighborhood,” “Málaga is my home, not your hostel,” “I’m closer to becoming a climate refugee than to being able to pay rent,” “Housing is not your plaything, it is a right.”

The meaning of others is still a little elusive. “Guiri is the new Cotorra” shows a parakeet with the face of a person with yellowish skin, big smile, bad teeth, sunglasses, and a bucket hat. A Guiri is an obnoxious, loud, normally pale-skinned but currently sun-burnt English-speaking tourist with no self-awareness; cotorras are the little green parrots I often see in the park, but the word (GPT tells me) also has a slang meaning — something like “loudmouth,” as best as I understand.

What’s confusing is the actual parakeets seem quiet and not at all annoying to me.

It’s the seagulls that are the problem.

I don’t think I’m a Guiri. I see and hear the drunk British tourists myself, and I get why the locals would have a word for their type. I am, however, a foreigner who rents an apartment in the historical center and has barely learned any Spanish in the 10 months he’s been here; Guiri or not, I do think I’m part of this protest’s agenda.

There’s an occasional Palestinian flag in the crowd. I don’t see the connection between the housing crisis in Málaga and the humanitarian crisis (is that what we’re calling it?) in Palestine.

A poster on a wall tries to make the connection for me. It says, “Zionists and Landlords, You Are on Our List.”

I think I’m on a list too, back in Russia — the last three times I crossed the border, which I haven’t done in more than two years, there was always an issue. It would have been nice to know for sure.

An empty shopping cart is left at the entrance of a local supermarket, with a handwritten sign taped to it: “This Carrefour Express will be a collection point to help families affected by Dana. Thank you.” It refers to the victims of a devastating flood that took lives of more than 200 people across Spain; I think one of them died in Málaga.

The extent of my troubles was that my dog was a little unnerved by the lighting during a particularly stormy night.

The cart is mostly empty. I put some canned food in it.

The art museum everybody says I should visit is named after Queen Sofia, the wife of King Juan Carlos I, who reigned from 1975 to 2014.

Juan Carlos was born in exile in Rome and became the ruler of Spain after the death of Franco, who named his successor himself, thus restoring the Spanish monarchy that had ended in 1931.

For the Russian mind, such movements of history are wild to consider. What if the Bolsheviks didn’t murder the entirety of the royal family? Would Russia’s monarchy be restored in 1991? Would that have been good? Maybe so.

Maybe it would have allowed for a separation of the sacred/ritualistic and the practical dimensions of state power.

In a recent “fates of the homeland” chat with a friend (something Russians do instead of drinking games), I propose a two-dynasty constitutional monarchy as a liberal reform that could fit the country’s profile: the actual governing power is shifted towards the prime minister and the parliament, while the symbolic power is put in the hands of a Tsar or Tsaritsa — a Putin or a Navalny, like the American Ds and Rs, chosen by vote after the death/abdication of the previous ruler from the same families.

The two-headedness of the eagle on Russia’s coat of arms would acquire a straight-forward, practical meaning.

The artist who drew the current version of that eagle (notable for, among other things, its fractal quality: it holds a scepter that ends with an eagle that holds a scepter, which presumably ends with an eagle that holds a scepter, and so on) was Yevgeny Ukhnalyov. As a young man he served 6 years in the camps, in the coal mines, in the 40s and 50s, for allegedly planning to dig a tunnel from Leningrad to Lenin’s Mausoleum in Moscow to perform a terrorist act. He was freed a year after Stalin’s death, with the stated reason being that “when committing the crime” he was not yet 18 years old.

In the Queen Sofia museum, in Madrid, I see things like this:

Any reader of Psychopolitica can book a one hour, one-on-one call with me by clicking the button below:

You will help me and Psychopolitica a great deal if you get a paid subscription.

Here’s a button for that:

Classifieds

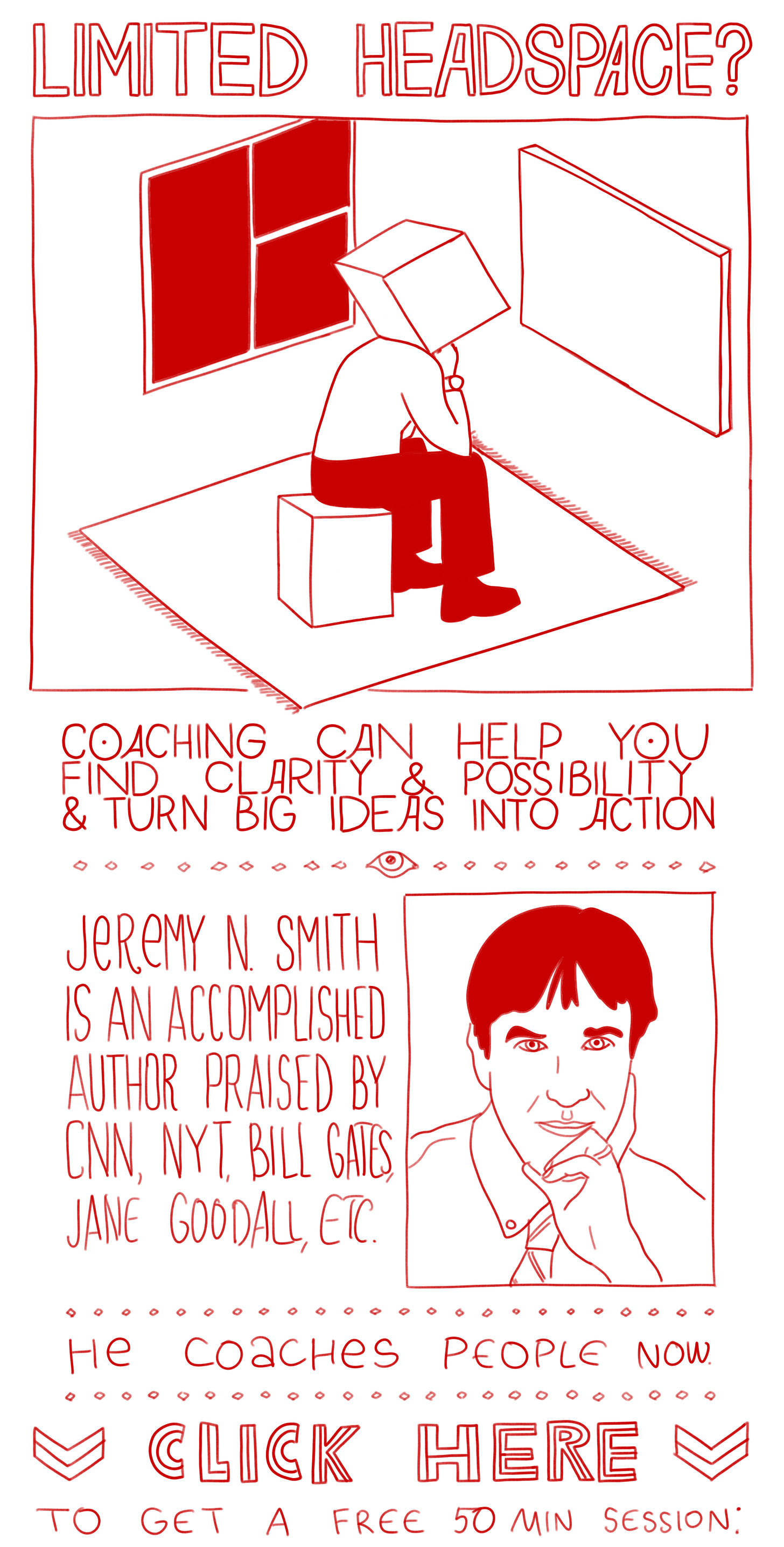

Jeremy N. Smith is a very accomplished coach, creative consultant, and writer acclaimed by CNN, the New York Times, Bill Gates, and Jane Goodall, among others.

He offers a complimentary coaching session to any PsyPol subscriber.

Thanks for this post. The details you include as the tales unfold are interesting. A nice set up to encourage internet rabbit hole reading.

I remember the English tourists in Greece in the 1980's. They really were far worse than even we loud Americans. The English didn't tip and drank horrible amounts of beer. There is some difference in beer drinkers. Beer drinkers love a crowd and act like everyone is with them,understanding the inside of their heads. Very different than brooding over whiskey or vodka. Like wine drinkers but without the food to temper it all.

Do you ever think of yourself as a conscientious objector? Muhammad Ali was convicted for refusing to go to war in Vietnam. He was able to have this overturned in the supreme court and did not serve time. Being wealthy and famous and american worked out okay for Ali. Russia,right now,is not a safe place to be an objector. A refugee of conscience is who I see in you and others who are expatriated from your home. Air b+b , absentee landlords ,private equity landlords-these are who people the world over are angry at.

Francis Bacon died in Madrid. I don't know if he painted while in the city. It would be interesting to find out if he spoke about any paintings he saw while in Madrid. I would see them and imagine him seeing them.

This is too wild! I thought a street sign (no pix) named "Indo Muerto" was bad. This truly is a topper!