Hey. Sorry for the long silence. My schedule has fallen apart under the weight of the day-to-day. Work, gas leaks, plumbing issues, a foreign country’s bureaucracy, intricacies of human connection, existential fatigue, a scorpion in the kitchen sink—juggling all this makes it hard to carve out enough time and attention to get any of my recent ideas to a publishable stage.

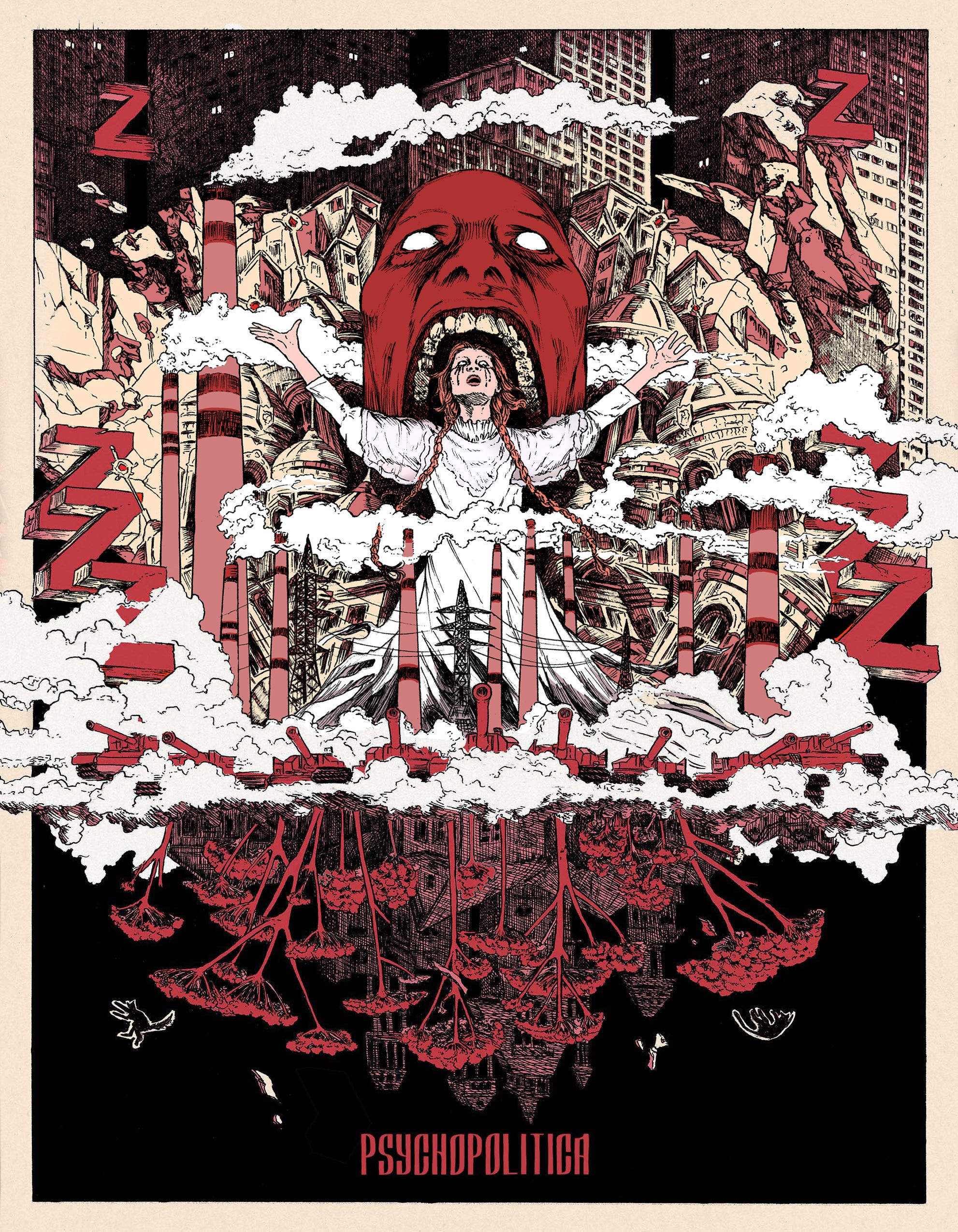

This post is my attempt to get out this ditch. I’ll try to tie some of my unfinished ideas together into a version of Psychopolitica’s future—a project I like to re-invent periodically—and then to get back to my normal weekly rhythm starting next Monday.

— NP

I have given up on writing a Russia/Ukraine op-ed for the NYT—I’m too close to the topic, my feelings on it too raw and my thoughts too hopeless and lacking conclusion.

I explained the decision in one of my drafts:

The paper’s editors understandably want a sustained original argument, and I am not sure developing one is appropriate in my situation. I’ve been managing, barely, to put words to my experiences here in PsyPol, but I can’t seem to bring myself up to formulating and sharing opinions.

If “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,” as Theodor Adorno (a German) pronounced, what should I think about writing op-eds after Bucha?

This is from a post that was supposed to be titled Russia’s Psychotic Break and whose draft got discarded when it reached 3,000 words. In it, I tried to explore alternative ways to talk about the war and adjacent issues: the spiritual degradation of Russia, the breakdown of its social reality, the vanishing of the future as a domain of planning and dreaming.

None of them worked, but one metaphor has become a seed of a new idea I’ve been lately intrigued by.

I wrote:

Post-Soviet Russia was like a troubled, quirky young woman—with her demons, a tendency towards unhealthy relationships, addictions, self-harm and violent outbursts—who still endeared some of us with her soulful late-night conversations, her dark sense of humor, her natural beauty. But her condition has been getting steadily worse—a dynamic supported by her abusive, gaslighting husband—and finally resulted in a violent psychotic break.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Psychopolitica to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.