I’m starting a regular podcast—new episode every other Monday—with my friend, science writer John Horgan. (There should be a subscribe button in the bottom-right of the player.)

Over time, I’m hoping to get to a weekly schedule, with other Mondays occupied by other guests.

In this first episode, John and I talked about John’s new book and hockey career, the 60s, my escape from the city, Russian new laws about “foreign agents” (and my case for not being one), my amanita muscaria project, the interplay between art and politics, Patti Smith and Adam Curtis, inner emigration, Psychopolitica, and more.

There’s a video version too:

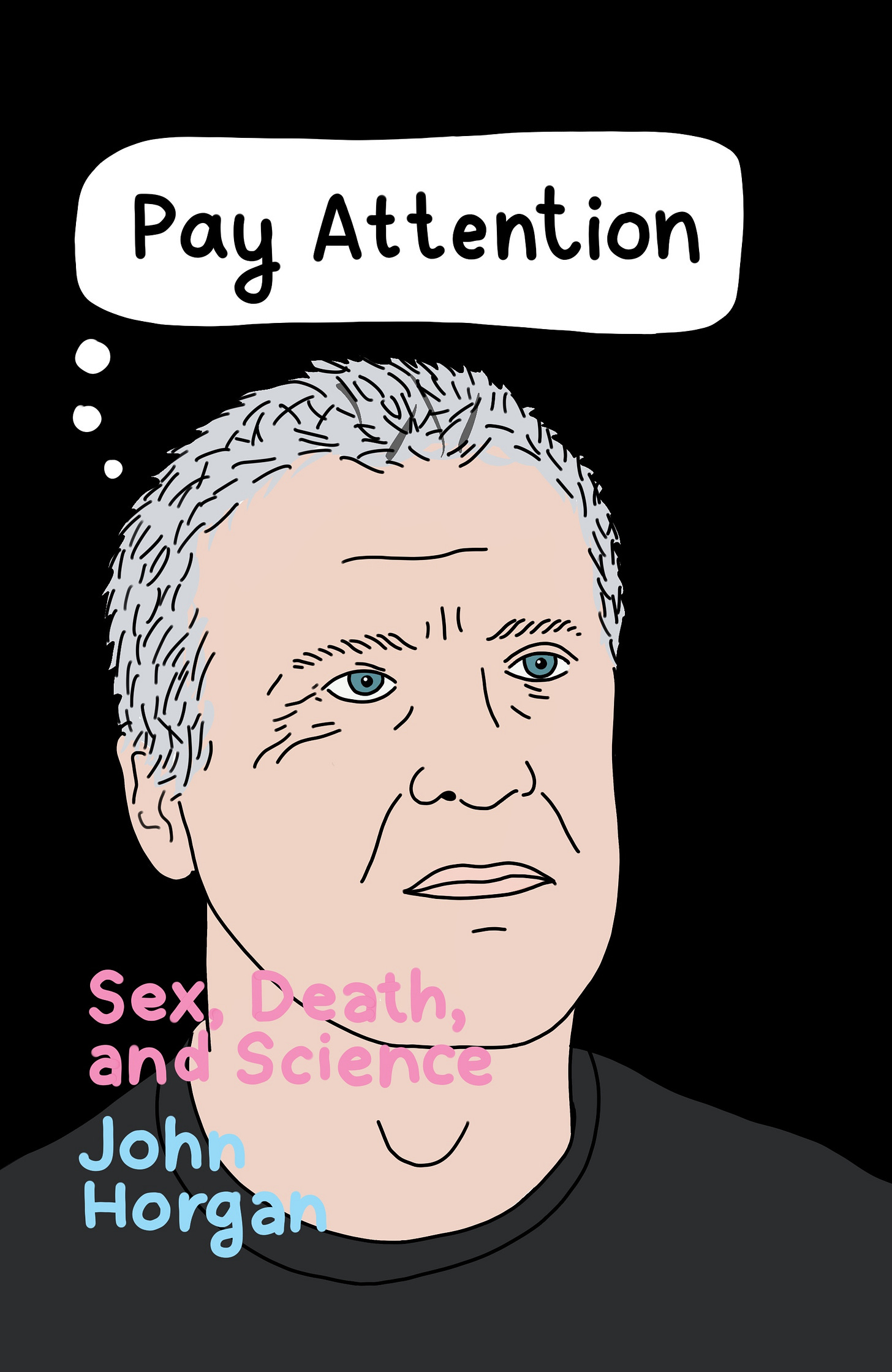

Below is a transcript of a 5 min segment from our conversation, which starts with John plugging his book—Pay Attention: Sex, Death, and Science—and quickly veers off into a disjointed monologue by me on politics, freedom, art, and the absurd.

The drawings are some of the illustrations I made for the book. They’ll seem out of context here, but maybe they’ll intrigue you enough to get the book on Amazon.

JOHN: People are sort of going, "Well, what is it? Is it like your other books? Is it a work of journalism?" And I'm not sure. It's hard for me to describe it. So I'm just trying to get people to go and read it, and then tell me what they think it is.

But as I said: kind of a stream of consciousness account of what a science writer thinks of over the course of a typical day.

NIKITA: I was actually a little skeptical when you told me the premise—a stream-of-consciousness thing, a day in life of a science writer—I thought, "Is a day in life of a science writer so captivating?"

But I loved it.

I'm always happy when a big, important, lofty thing—something you're supposed to care about, political or philosophical or whatever—is contextualized in the actual experience of life, and it turns out that these ideas about whether consciousness or matter is the primary thing and the other secondary are right there next to... I think the book starts with the question "Who farted?"

Like, that is how it actually works.

The big philosophical opinions, decisions and ideas are right next to the mundane and the absurd. And I love that.

I once had an experience of the same kind of thing, but in the political realm. I went to three different events in the course of a week.

One was this thing called Monstration.

It’s a weird tradition that started about 15 years ago in Russia. It's something that looks like a political rally that's done on the 1st of May, which was this huge thing for the Soviet state and ideology—Labor Day, you know, workers of the world unite—and then the holiday carried over, so everybody gets a day off; but the ideology is not there anymore, so it's sort of unclear why this is a big holiday. And these rallies still take place, various political forces do their thing, but, again, it's not always clear why.

And so somebody came up with the idea of doing something that looks like a political rally, but with all the slogans being puns, or absurdities, or something, the meaning of which is hard to be sure about. Some of these are political jokes, but most are just a way to appreciate the absurd.

The one I participated in, in St. Petersburg, was interesting in format. They couldn't get a separate permit for the Monstration, but the city allowed to make it a part of everybody else's demonstration. And this made it even better.

You had these Stalinists—who were not making any jokes, they were actually proudly carrying porters of Stalin, marching down the street—and after them there were anarchists, and after them nationalists, and then you had these other people, and it wasn’t clear what they were up to. It made things even more absurd.

You could see the faces of the cops watching the thing: they could place the communists in one bucket, and the anarchists in another, and then they saw us, and we made them confused.

They’d see one poster that did mention Putin among a dozen of nonsensical ones, and discuss: Should we grab that person? Is that a violation of whatever it is that we're defending here?

Somebody waved from a window of a nearby building as the crowd was walking past. People started chanting: That dude in the building! That dude in the building! So the man hears a whole procession of people just chanting his presence.

At some point, the rally made a turn in a direction people didn't expect. So the Monstration crowd started chanting, Where are we going? Where are we going?

It seemed like a beautiful metaphor both for this march—not just this subset of it, but the Stalinists on the anarchists and everybody else too—and also the country itself, not knowing where it is headed, confused about the purpose of it all.

Sorry, I'm taking a long time to get to my point.

I went to this thing, and the second event was a music show by this young singer—a girl who had just finished high school, she must have been 18 or so at the time.

She was not assuming a political pose of any sort. She wasn't not trying to be heroic and stand up to Putin. But politics is present in her songs as references, as something to make a joke or a rhyme about. And there were things in those songs that could be framed as inciting violence against the police, but they were situated in between the first love and getting drunk as a teenager, and whatever else an 18 year old girl has on her mind. First love, stealing whiskey from dad—and then, Putin, the war in Crimea, and the police state.

And finally, there was an actual political rally, organized by Navalny's people, against Putin's inauguration for his new term at a time.

And my sense was that the people at the overtly political rally looked like people who really want to be free but can’t. They live under this oppressive regime. So they need to get Putin out, and then they’ll be free—at some future point.

While the people at the absurdist rally and these young kids at the music show seemed like people who are already free, despite Putin and his police state.

They're not held back in terms of their individual freedom. They're not scared to be honest in their self-expression, to do what they want to do, be what they want to be—as opposed to this other approach, "First we're going to fight Putin, and then afterwards we're going to be able to do what we want to do."

So your book has that quality for me. It's not in the political realm. It's in the philosophical, scientific area of thought. But there is that quality still—the big, important thing is contextualized in the actual lived experience. And the actual lived experience is more important to me than these systems of thought that we construct.

Thank you. I think you, maybe more than anybody, get what I was after, and I'm sure it helps that we've had these conversations over the years.

I've always been struck by the disconnect between ideas in my head—in the way that I think about them and the way that they're all entangled with all this other stuff that's going on in my head...

Like, if I'm writing an essay about free will, there's my argument for free will on the page, and it doesn't even have that much to do with what's actually going on in my head when I'm thinking about free will. When I'm having all these doubts, and then thinking about my girlfriend or about my kids, having all these emotions swirling around...

So the older I get, the more it seems to me that, when ideas are lifted out of their human context and presented in papers and books, they are phony somehow. They're not real when they're pulled out of their context.

Share this post